Key Takeaways

- Matcha is better for energy and blood sugar than chai, which is often prepared with sweeteners and milk.

- Preparation matters. Added sugars and milk choices, not the tea leaves or spices, drive energy and glucose responses between chai and matcha.

- Whether you choose chai or matcha is personal and measurable. Track your response with a continuous glucose monitor to help identify which tea and preparation method supports stable energy for you.

that {{mid-cta}}

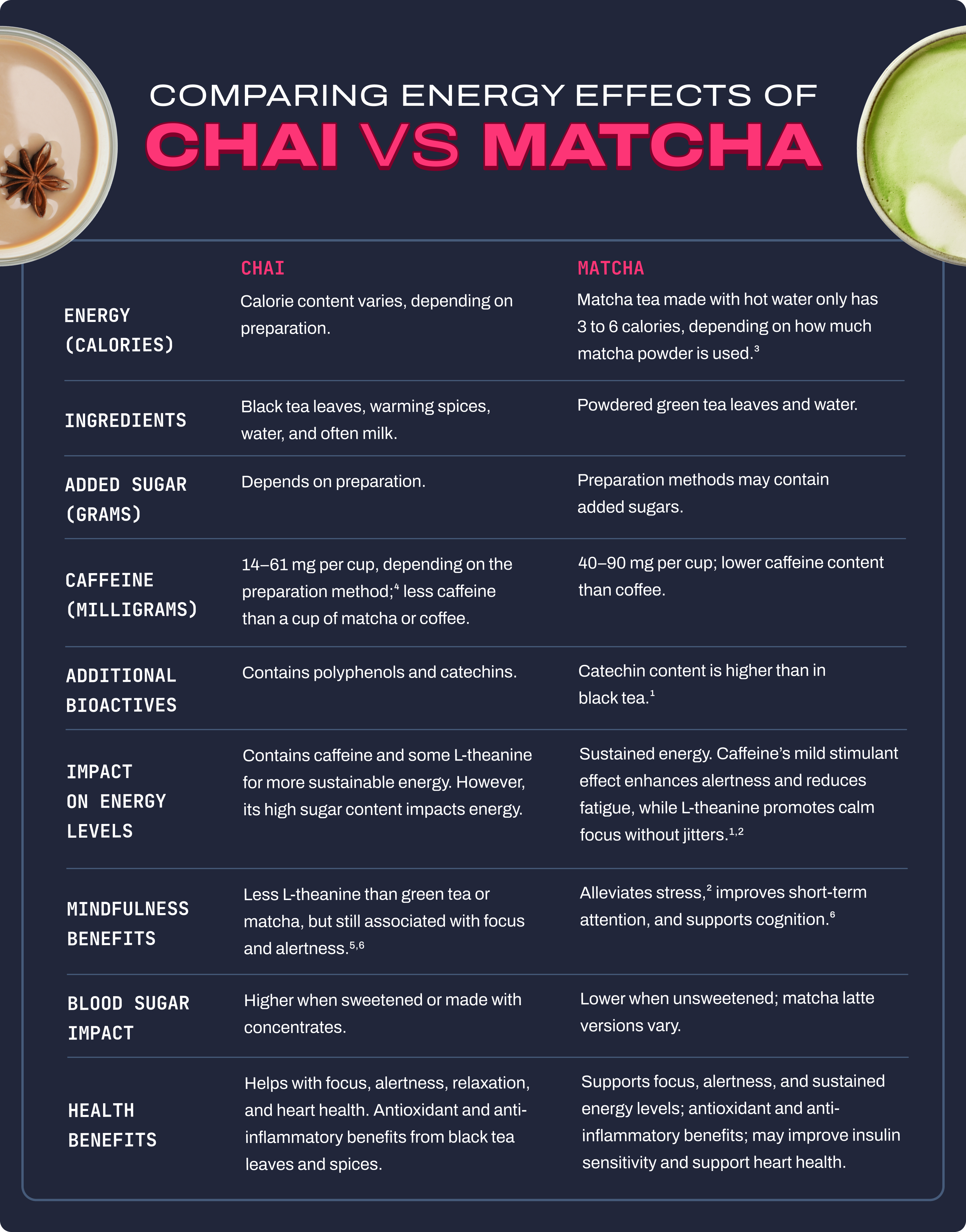

Tea is a go-to for an afternoon energy boost without the caffeine of coffee. But when it comes to energy and blood sugar, the details matter. Chai and matcha may look similar on the menu, yet differences in caffeine, added sugar, and preparation can lead to significant differences in glucose response.

Knowing how each tea affects energy and glucose variability can help you choose the option that keeps you alert without the spike-and-crash.

What Is Chai?

Chai (masala chai) is typically made with black tea leaves brewed alongside warming spices like cardamom, ginger, cloves, and black pepper. Because it’s derived from black tea, chai provides caffeine plus polyphenols that may support antioxidant and anti-inflammatory pathways.

While the spices themselves contain beneficial plant compounds, chai’s impact on energy and blood sugar heavily depends on how it’s prepared. Traditional and cafe-style chai is often made with milk and added sugar, and premade chai concentrates can contain significant amounts of sugar per serving. These added sugars, not the tea or spices, drive larger post-drink glucose spikes and greater glucose variability, which may translate to less stable energy levels throughout the day.

What Is Matcha?

Matcha is a finely powdered green tea made from Japanese shade-grown tea leaves, a growing process that enhances its bioactive and caffeine content. Unlike brewed green tea, matcha involves consuming the whole-leaf powder, providing a higher concentration of antioxidants and nutrients.

Matcha is packed with polyphenols, specifically catechins like epigallocatechin-gallate (EGCG), which contribute significant antioxidant properties and may be associated with better physical and mental health. It also contains L-theanine, an amino acid that contributes to matcha’s unique flavor profile and interacts with caffeine to promote alertness with a calmer, more focused feel.1,2 For many people, the combination of caffeine and L-theanine supports sustained energy without jitters.

Compared to other green teas, matcha has a high caffeine content, delivering about 40-90 mg per cup of matcha, depending on how much powder you use.1

Like chai, matcha’s glucose impact may depend on preparation. Plain matcha made with hot water contains virtually no sugar, while premade matcha drinks and lattes may include sweeteners that can significantly alter the glucose response.

Comparing Energy Effects

Blood Sugar and Metabolic Impact

The biggest difference between chai and matcha isn’t the tea; it’s what’s added to it. Sweetened chai, especially from coffee shops or concentrates, often contains enough added sugar to trigger a rapid glucose rise.

Matcha tends to be more glucose-stable when prepared plain. It contains minimal sugar and delivers catechins that may support insulin sensitivity. When matcha is made into a latte, glucose responses depend largely on milk choice and any added sugar.

Adding milk to a chai latte or matcha latte introduces lactose, increasing the carbohydrate content. However, the accompanying protein and fat may help blunt glucose spikes for some people. Still, glucose responses to chai and matcha lattes can vary widely from person to person.

Whole, low-fat, and nonfat milk can each produce distinct glucose patterns, making glucose tracking and side-by-side comparisons useful. Plant-based milks can further shift the glucose response. Unsweetened almond milk is low in carbohydrates and often results in a smaller post-drink glucose rise compared to dairy milk, though responses still vary between individuals.

Use your CGM to compare chai vs. matcha, latte vs. plain, and different milk options to identify which preparation supports steadier energy and lower glucose variability for you.

Other Health Considerations

Beyond its effects on energy and glucose, compounds in chai tea and matcha may offer additional health benefits.

- Antioxidants: Tea is a potent source of antioxidants, with the type and capacity varying between teas. Tea polyphenols scavenge free radicals, reducing inflammation and minimizing cell damage.7

- Anti-inflammatory: Catechins in matcha may help reduce inflammation by altering the production of inflammatory cytokines.1 Other compounds in tea regulate inflammatory pathways.7

- Supports heart health: Regularly drinking tea, without added sugars, is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular events. Bioactives in tea help relieve atherosclerosis and may promote vasodilation, reducing stress on the arteries.7

- May support insulin sensitivity: Catechins in matcha may influence liver glucose production, insulin signaling, and oxidative stress, making your body more responsive to insulin and leading to steadier glucose levels.8

- May aid gut health: Bioactive compounds in warming spices in chai tea may encourage digestion by supporting motility and reducing nausea. Specifically, ginger may reduce nausea and inflammation, improving upper gastrointestinal symptoms.9 Cinnamon and cloves may provide antimicrobial and antispasmodic effects, while cardamom may support intestinal mucosal lining.10,11,12

How to Optimize Tea for Energy and Glucose Stability

- Make chai or matcha yourself. Making matcha or chai at home gives you full control over added sugars and portion sizes. Start with plain matcha or loose-leaf chai tea and use sweeteners minimally, if at all.

- Skip or limit added sugar. Added sugars, not the tea, are the biggest drivers of glucose spikes and energy crashes. Ditch the sugar for a more glucose-friendly tea that supports stable energy.

- Choose unsweetened or lightly sweetened versions. When you’re out, choose unsweetened or lightly sweetened chai or matcha, or ask for fewer syrup or concentrate pumps. If unsweetened options aren’t available, plain black or green tea can deliver caffeine and polyphenols without the added sugar and effect on glucose.

- Pair with milk or unsweetened soy milk. Milk or unsweetened soy milk adds protein and fat, which can slow glucose absorption and support more stable blood sugar responses.

- Track your glucose responses. Use a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) to track how your body responds to chai and matcha.

- Run small experiments. Compare your glucose response to chai or matcha with and without milk, or try different timing (morning vs. mid-afternoon) to see what supports alertness without disrupting sleep or increasing glucose variability.

The Bottom Line

.png)

Both chai and matcha provide caffeine and bioactive compounds that support energy and overall health. However, one clear difference exists: matcha tea prepared without added sugar tends to produce more stable glucose responses and more sustained energy.

Chai can still fit into a glucose-conscious routine, but sweetened versions are more likely to drive glucose spikes.

Personalized tracking with Signos can help you understand how each tea affects your energy, focus, and glucose, so you can make the best choice for your day.

Learn More With Signos’ Expert Advice

Discover how Signos can improve health to help you move from guessing to data-driven decisions about glucose, energy, and metabolic health. With continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and the Signos app, you can see how foods, drinks, timing, and combinations impact your glucose and energy.

Learn more about how different foods can affect glucose on Signos’ expert-written blog.

Topics discussed in this article:

References

1. Kochman, J., Jakubczyk, K., Antoniewicz, J., Mruk, H., & Janda, K. (2020). Health benefits and chemical composition of matcha green tea: A review. Molecules, 26(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26010085

2. Unno, K., Furushima, D., Hamamoto, S., Iguchi, K., Yamada, H., Morita, A., Horie, H., & Nakamura, Y. (2018). Stress-reducing function of matcha green tea in animal experiments and clinical trials. Nutrients, 10(10), 1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10101468

3. Phuah, Y. Q., Chang, S. K., Ng, W. J., Lam, M. Q., & Ee, K. Y. (2023). A review on matcha: Chemical composition, health benefits, with insights on its quality control by applying chemometrics and multi-omics. Food Research International, 170, 113007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2023.113007

4. Chin, J. M., Merves, M. L., Goldberger, B. A., Sampson-Cone, A., & Cone, E. J. (2008). Caffeine content of brewed teas. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 32(8), 702–704. https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/32.8.702

5. Boros, K., Jedlinszki, N., & Csupor, D. (2016). Theanine and Caffeine Content of Infusions Prepared from Commercial Tea Samples. Pharmacognosy magazine, 12(45), 75–79. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1296.176061

6. Anas Sohail, A., Ortiz, F., Varghese, T., Fabara, S. P., Batth, A. S., Sandesara, D. P., Sabir, A., Khurana, M., Datta, S., & Patel, U. K. (2021). The Cognitive-Enhancing Outcomes of Caffeine and L-theanine: A Systematic Review. Cureus, 13(12), e20828. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.20828

7. Shang, A., Li, J., Zhou, D.-D., Gan, R.-Y., & Li, H.-B. (2021). Molecular mechanisms underlying health benefits of tea compounds. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 172, 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.06.006

8. Wen, L., Wu, D., Tan, X., Zhong, M., Xing, J., Li, W., Li, D., & Cao, F. (2022). The Role of Catechins in Regulating Diabetes: An Update Review. Nutrients, 14(21), 4681. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214681

9. Aregawi, L. G., Shokrolahi, M., Gebremeskel, T. G., & Zoltan, C. (2023). The Effect of Ginger Supplementation on the Improvement of Dyspeptic Symptoms in Patients With Functional Dyspepsia. Cureus, 15(9), e46061. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.46061

10. Yahyazadeh, R., Ghasemzadeh Rahbardar, M., Razavi, B. M., Karimi, G., & Hosseinzadeh, H. (2021). The effect of Elettaria cardamomum (cardamom) on the metabolic syndrome: Narrative review. Iranian journal of basic medical sciences, 24(11), 1462–1469. https://doi.org/10.22038/IJBMS.2021.54417.12228

11. Tariq, H., Alhudhaibi, A. M., & Abdallah, E. M. (2025). Syzygium aromaticum (clove buds) as a natural antibacterial agent: a promising alternative to combat multidrug-resistant bacteria. Frontiers in microbiology, 16, 1674590. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1674590

12. Nabavi, S. F., Di Lorenzo, A., Izadi, M., Sobarzo-Sánchez, E., Daglia, M., & Nabavi, S. M. (2015). Antibacterial Effects of Cinnamon: From Farm to Food, Cosmetic and Pharmaceutical Industries. Nutrients, 7(9), 7729–7748. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7095359

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)