Many people believe that diet and food choices are the most important things when it comes to weight loss, but you might be surprised to know that when you eat can also play a role. Meal timing can affect fat loss because the time of day impacts hormone levels, insulin sensitivity, and your body’s glucose response.1 Changes in insulin sensitivity and blood glucose can influence energy levels, appetite, and fat storage, sometimes independently of the foods you’re eating.

Irregular eating patterns, such as skipped meals and late dinners, are common, especially among people managing long days, caregiving responsibilities, and hectic schedules. In many cases, these habits aren't intentional; they're a reaction to real life. Regardless, they can be a hindrance if you’re trying to lose weight.

Glucose and insulin responses vary from person to person, and no two individuals respond to meal timing the same way. That’s why generalized advice doesn’t always work for everyone. Identifying your own individual responses becomes possible with a continuous glucose monitor (CGM). CGM data can help you understand how your habits and patterns, including meal timing, affect your blood sugar and weight loss goals. Below, we discuss common meal-timing challenges, how they affect blood sugar, and how CGM data can guide more individualized adjustments.

Best Meal Time for Weight Loss: Morning Glucose Response and Fat Loss

.png)

For most people, the body is most responsive to insulin in the morning, which can make glucose easier to manage after meals.2 For some, this creates a metabolic advantage earlier in the day, allowing carbohydrates to be used more efficiently for energy rather than stored. When the first meal is delayed or skipped entirely, that window may be shortened or missed. Studies suggest that eating earlier in the day (particularly breakfast) is associated with better insulin sensitivity and glucose control than skipping breakfast or shifting more calories to later meals.3

While most people have better insulin sensitivity in the morning and can benefit from eating a balanced breakfast, this isn’t the case for everyone. Some people experience sharp blood sugar rises after breakfast, particularly when meals are low in protein or fiber and higher in refined carbohydrates. Others see relatively stable responses to similar foods. These differences help explain why eating breakfast supports fat loss for some individuals but may be counterproductive for others.

When blood sugar rises quickly in the morning, it can trigger a stronger insulin response early in the day. For some people, that sets off a pattern of energy dips and increased hunger later on, often leading to larger meals or more frequent snacking by afternoon or evening. In contrast, a slower, more gradual rise in blood sugar after the first meal is often followed by steadier energy and appetite, which can make overall intake easier to regulate across the day.

A continuous glucose monitor (CGM) helps you to determine which camp you fall under. CGM data can show how your body responds to eating breakfast, whether glucose spikes rapidly, how long it takes to return to baseline, and whether that response influences glucose levels later in the day. Some people find that adjusting the timing of their first meal, or the nutrient composition, leads to smoother glucose curves and fewer swings in appetite, while others learn that skipping or delaying breakfast has little effect. The value lies in seeing how morning meal timing affects your individual glucose pattern and how that may be affecting your weight-loss goals.

CGM and Weight Loss: Skipping Meals and Blood Sugar Stability

.png)

Whether meals are skipped as an intentional weight-loss tactic or simply because of a busy schedule, doing so alters how the body responds to the next meal. When food intake is delayed for several hours, blood sugar may drop below optimal levels.

To maintain glucose availability, the body increases the release of counterregulatory hormones such as glucagon and cortisol.4 This response is normal, but it can leave the body less prepared to handle incoming carbohydrates from the next meal. As a result, eating may trigger a larger or more rapid rise in blood sugar than the same meal eaten after a shorter interval.

Recent research highlights that the metabolic impact of skipping meals depends on which meal is skipped. In a controlled study using continuous glucose monitoring, skipping lunch for two consecutive days significantly increased post-dinner blood glucose levels compared with days when lunch was eaten, even when calorie and carbohydrate intake were similar.

Skipping breakfast raised glucose after lunch, but the effect was more limited, while skipping dinner did not significantly worsen glucose responses at the following meal.5 These findings suggest that prolonged gaps earlier in the day, particularly between breakfast and dinner, may be more disruptive to glucose regulation than skipping later meals.

From a fat-loss perspective, these glucose patterns matter. Larger post-meal glucose excursions typically require a stronger insulin response, and insulin suppresses fat breakdown while favoring energy storage.6 Repeated spikes and greater variability can also make appetite harder to regulate, increasing the likelihood of larger meals later in the day, often when insulin sensitivity is already lower.

A continuous glucose monitor helps bring these effects into focus. CGM data can reveal blood sugar trends during long stretches without food and how the body responds once eating resumes. Some people see pronounced drops followed by sharp post-meal rises, while others experience elevated or highly variable glucose levels well into the evening. Seeing these patterns makes it easier to evaluate whether skipping meals supports or undermines blood sugar stability, and whether changes in meal timing, spacing, or consistency improve the overall glucose response.

Eating Time Schedule for Weight Loss: How Late Eating Can Affect Blood Sugar Patterns

.png)

Many people end up eating most of their calories late in the evening, sometimes well into the night. When food intake shifts later in the day, it’s processed under different metabolic conditions than it would be in the morning and early afternoon.

Glucose tolerance is typically lower at night, which may lead to larger spikes in blood sugar, followed by prolonged elevations. Insulin sensitivity also decreases, so the body requires more insulin to manage glucose than it did earlier in the day.2

Over time, repeated exposure to higher evening insulin levels can make blood sugar regulation more difficult, particularly when late meals are large or carbohydrate-heavy. When insulin remains elevated for longer periods, the body is more likely to store energy than use fat for fuel.6

Research supports this pattern. In weight-loss programs where calorie intake and diet quality were comparable, participants who ate a greater share of their daily calories later in the day showed lower insulin sensitivity and lost less weight than those who ate earlier. Other studies have linked later dinner timing (after 8 p.m.) with higher hemoglobin A1c levels, suggesting that the effects of late eating may extend beyond individual meals to longer-term glucose control.7

Circadian rhythm is likely a key driver. Metabolic processes follow a daily cycle, with greater efficiency earlier in the day and a gradual slowdown at night.1,2 Eating against that rhythm doesn’t automatically lead to weight gain, but it can reduce how efficiently the body handles glucose and energy when late eating becomes a consistent pattern.

A CGM makes the effects of late eating easier to see. CGM data can show whether blood sugar stays elevated overnight, fluctuates during sleep, or rises unexpectedly the next morning after a late meal. Some people see higher post-dinner glucose levels that linger for hours, while others notice greater variability or delayed responses. Seeing these patterns removes guesswork and allows you to understand how timing interacts with individual physiology—whether changes in when you eat, what you eat, or how consistently you eat alter the glucose response.

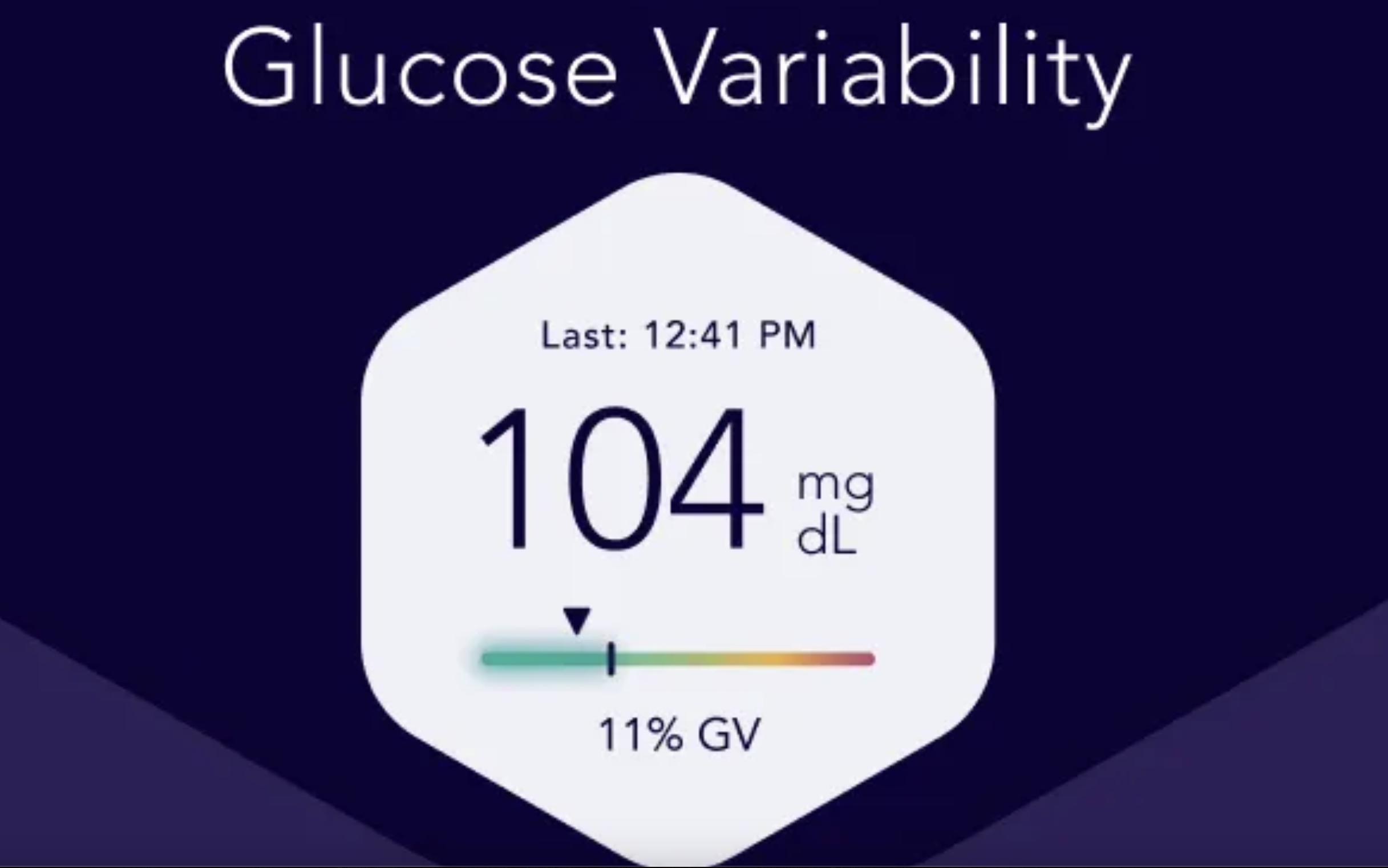

Weight Loss With CGM: Glucose Variability From Irregular Meal Timing

Irregular meal timing refers to eating meals at different times from day to day, even when total intake stays similar. This lack of consistency can interfere with the body’s ability to anticipate and regulate blood sugar, leading to increased glucose variability rather than a stable response.

Glucose regulation follows a daily pattern tied to circadian rhythm.1,2 When eating is unpredictable, that rhythm becomes harder for the body to anticipate. The result, for some people, is greater glucose variability (larger swings between highs and lows) rather than consistently elevated levels. These fluctuations can increase the overall insulin demand required to manage blood sugar across the day.

Higher glucose variability matters for weight loss because it can influence both energy use and appetite regulation. Rapid rises and falls in blood sugar are often followed by shifts in hunger, cravings, or energy levels that make maintaining eating patterns harder.8 Over time, this variability can work against fat loss by increasing the likelihood of compensatory eating, particularly later in the day when insulin sensitivity is already lower.

A continuous glucose monitor helps identify whether irregular timing is contributing to these patterns. CGM data can reveal how blood sugar responds on days when meals are spaced and timed consistently compared with days when eating times vary widely. Some people notice smoother glucose curves when meals occur at similar times each day, even if the foods themselves don’t change. Others see little difference, suggesting that timing consistency matters less than other factors.

Adding visibility to these trends allows individuals to evaluate whether greater regularity in meal timing supports more stable glucose patterns. Rather than enforcing rigid schedules, CGM insights help clarify whether consistency itself (independent of meal frequency or food choice) plays a role in blood sugar variability and, ultimately, weight loss progress.

Eating Time Schedule to Lose Weight: Why One-Size-Fits-All Eating Windows Fall Short

.jpg)

Eating windows, such as early time-restricted eating (TRE), intermittent fasting (IF), or fixed cutoff times for meals, are often presented as universal solutions for weight loss. While these approaches can be effective for some people, their results are far from consistent. The metabolic response to eating within a specific window varies widely, influenced by factors such as insulin sensitivity, circadian rhythm, activity level, sleep patterns, and baseline glucose regulation.

While some research shows that IF and TRE may have some health benefits, including weight loss, other studies suggest that there is no benefit when calorie intake and diet quality are similar.9,10 Some individuals have great success with IF and TRE, but when eating windows conflict with hunger cues, work schedules, or sleep timing, they can have the opposite effect: leading to larger meals, greater glucose excursions, or increased variability once eating resumes.

From a glucose perspective, the issue isn’t the length of the eating window alone, but how consistently the body can anticipate food intake. Abruptly compressing meals into a narrow time frame may increase post-meal glucose responses for some people, particularly if meals become larger or more carbohydrate-dense to compensate for longer fasting periods. Others may experience more stable glucose patterns with a longer or more flexible window that better matches their natural rhythms.

CGM data helps clarify whether a specific eating window supports or interferes with your blood sugar management and weight loss goals. Using a CGM, you can compare glucose patterns across different time-restricted eating patterns and see whether shorter eating windows improve glucose stability. Some people find that small adjustments, such as changing the timing of the first and last meals, are enough to make a difference.

Weight loss depends not only on when eating starts and stops, but on how meal timing interacts with glucose regulation, appetite, and daily routines. CGM insights allow eating windows to be adapted rather than imposed, helping individuals identify schedules that support both blood sugar stability and long-term adherence.

Bottom Line

Meal timing can influence weight loss by affecting how the body regulates blood sugar, insulin, and appetite throughout the day. Meal timing responses vary widely from person to person. Patterns like skipping meals, eating late at night, or following rigid eating windows may support fat loss for some individuals and work against it for others. A continuous glucose monitor helps you identify how meal timing interacts with your own physiology. Rather than following one-size-fits-all rules, CGM data takes the guesswork out of meal timing, supporting stable blood sugar and sustainable weight loss over time.

Learn More With Signos’ Expert Advice

Learn how Signos can improve your health with expert guidance to help you interpret glucose patterns and understand how factors like meal timing can affect your metabolic health. Explore Signos’ science-backed, expert-written blog to learn more.

Topics discussed in this article:

References

- Poggiogalle E, Jamshed H, Peterson CM. Circadian regulation of glucose, lipid, and energy metabolism in humans. Metabolism. 2018;84:11-27. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2017.11.017

- Fujimoto R, Ohta Y, Masuda K, et al. Metabolic state switches between morning and evening in association with circadian clock in people without diabetes. J Diabetes Investig. 2022;13(9):1496-1505. doi:10.1111/jdi.13810

- Maki KC, Phillips-Eakley AK, Smith KN. The Effects of Breakfast Consumption and Composition on Metabolic Wellness with a Focus on Carbohydrate Metabolism. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(3):613S-21S. Published 2016 May 16. doi:10.3945/an.115.010314

- Venugopal SK, Sankar P, Jialal I. Physiology, Glucagon. [Updated 2023 Mar 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537082/

- Kanazawa C, Shimba Y, Toyonaga S, Nakamura F, Hosaka T. Effects of skipping breakfast, lunch or dinner on subsequent postprandial blood glucose levels among healthy young adults. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2025;22(1):76. Published 2025 Jul 16. doi:10.1186/s12986-025-00975-4

- Ludwig DS, Ebbeling CB. The Carbohydrate-Insulin Model of Obesity: Beyond "Calories In, Calories Out". JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1098-1103. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2933

- Rangaraj VR, Siddula A, Burgess HJ, Pannain S, Knutson KL. Association between Timing of Energy Intake and Insulin Sensitivity: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):503. Published 2020 Feb 16. doi:10.3390/nu12020503

- Wyatt P, Berry SE, Finlayson G, et al. Postprandial glycaemic dips predict appetite and energy intake in healthy individuals. Nat Metab. 2021;3(4):523-529. doi:10.1038/s42255-021-00383-x

- Ezpeleta M, Cienfuegos S, Lin S, et al. Time-restricted eating: Watching the clock to treat obesity. Cell Metab. 2024;36(2):301-314. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2023.12.004

- Liu D, Huang Y, Huang C, et al. Calorie Restriction with or without Time-Restricted Eating in Weight Loss. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(16):1495-1504. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2114833

.jpg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)